An Interview with Dr. Paul Ekman

Paul Ekman, PhD. / Paul Ekman Group, LLC

Have you ever looked at someone’s face and wished that, somehow, you could tell what they were thinking? Wondered whether you could, somehow, tell whether they were lying? It turns out, you can. Decades ago, Paul Ekman, a young research psychologist, decided to dedicate himself to a major mystery that was just waiting in plain sight — the face.

Over the course of many years and studies, Dr. Ekman co-discovered something extraordinary: micro-expressions, lightning-fast facial expressions revealing subjects’ true feelings — even when they tried their best to hide them. With his colleague Wally Friesen, Dr. Ekman developed a system to catalog these facial expressions and, subsequently, became a sought-after expert on emotions and facial expressions. He wrote Emotions Revealed, a primer on reading faces, served as the scientific consultant on Pixar’s Inside Out, and crafted trainings for actors, law enforcement personnel, and the general public. Time magazine cited Dr. Ekman as one of the 100 most influential people; Malcolm Gladwell interviewed him for the New Yorker.

We were fortunate to get to meet Dr. Ekman when we worked with him to produce Moving Toward Global Compassion, a book exploring empathy and altruism, featuring an interview with the Dalai Lama. Later on, we connected Dr. Ekman with Eric Rodenbeck, who assisted him and the Dalai Lama in creating the Atlas of Emotions, an interactive tool that helps users better understand the vocabulary of their own emotions.

We sat down with Dr. Ekman to talk with him about why the face is like Mount Everest, how he met the Dalai Lama, and what it means to live a good life.

How did you first get interested in the face?

PE: Many years ago, I submitted an article to a journal, hoping they would publish it. They wrote back and said, “We’ve had an article submitted by a much older psychologist that deals with similar issues as yours. You two ought to meet.”

So, I flew back to the East Coast and met Silvan Tomkins. We got along splendidly, and he’s responsible for interesting me in the face. Tompkins was able to get information from looking at facial expression that no one I’d ever met could. He told me he’d learned to read the face by studying the expressions of his young child.

I remember saying, “What you can get out of facial expression is just extraordinary. I’m going to take it upon myself to try to develop the tools that will allow anyone to see and understand what you are seeing and understanding.”

That’s how I got started on looking at faces.

How long did it take, studying and decoding the face?

PE: It was a very slow process, to do it systematically and to catalogue it. No one had ever done it before! It took about six years.

In the course of your research, what did you learn?

PE: Most facial expressions last between a quarter of a second and a second and a half. If [the expressions] are on the face longer than that, they’re probably not genuine. But a micro-facial expression is there for a twenty-fifth of a second. Another person discovered [micro-facial expressions] at the same time. We differed in only one respect.

He thought that you wouldn’t be able to see [micro-facial expressions] unless you used slow-motion. And I’ve found that you could train people in under an hour, so they could see [a micro-facial expression] without slow-motion.

How can people see those expressions?

PE: I worked with Wally Friesen, my associate, on the development of the Facial Action Coding System, FACS for short. That’s the gold standard — cataloguing what the face is actually showing, muscular action. You know, if I narrow the red margin of my lips, Muscle 23 is the one that’s doing that.

What does that mean, when Muscle 23 does that?

PE: 23 is generally a highly reliable sign of anger unexpressed.

It’s just amazing what fun I’ve had, cataloguing the face. It’s amazing how complicated the face is, and it was waiting for me. No one had thoroughly explored it. It was like Mount Everest, waiting for me to ascend it, and make it accessible and understandable and researchable. What a good time I had. Awfully good time. And I met such interesting people as a result, animators, cartoonists. I spent six months in New York teaching actors.

I know that your work, studying faces, ties into other research that you’ve done, studying the emotions. What have you found, from studying about the emotions?

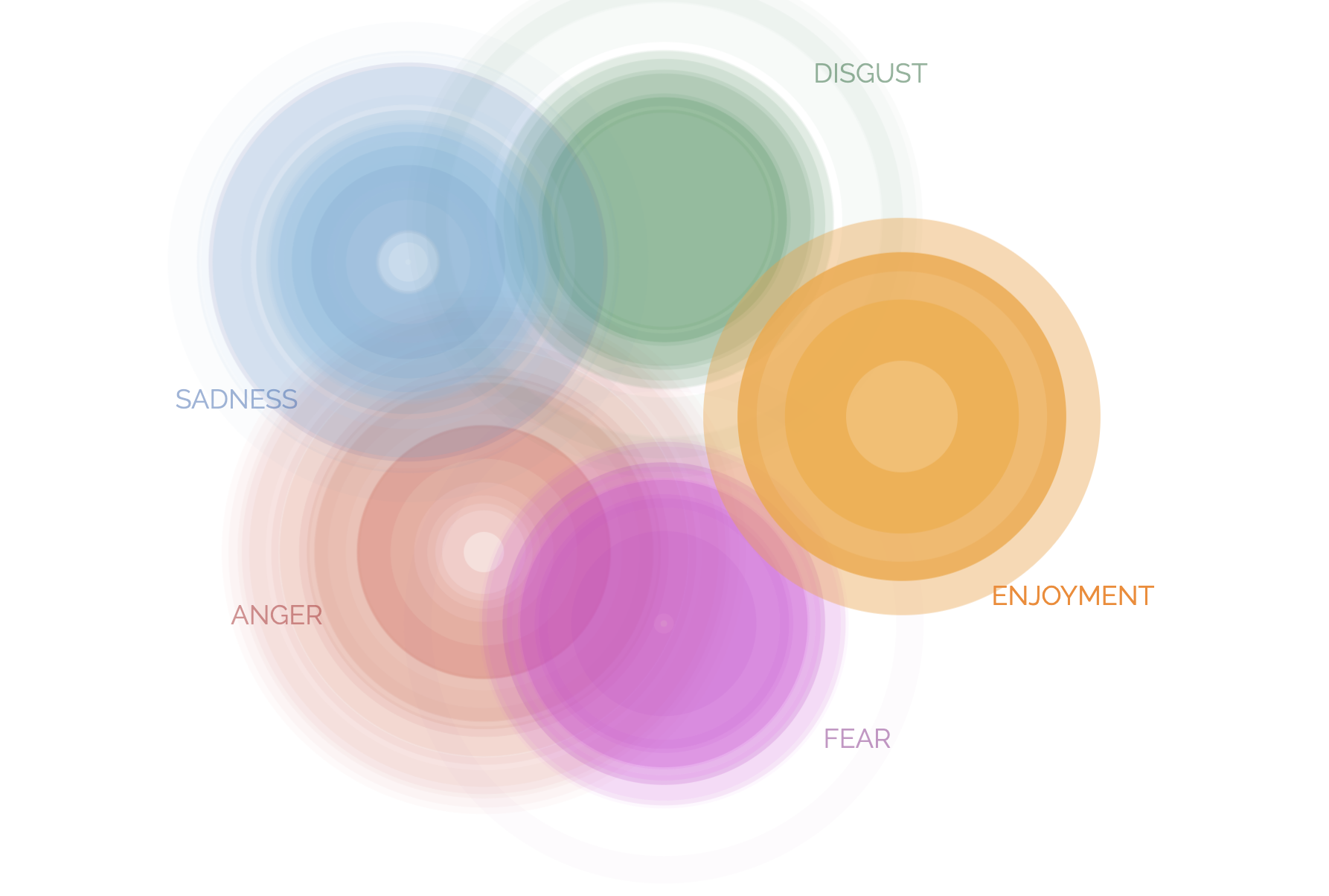

PE: I published evidence that six to seven emotions are universal to our species, and they’re also found in the great apes. The one [emotion] that there’s uncertainty about is surprise, because surprise is hedonically neutral — it’s neither pleasant nor unpleasant, intrinsically. It’s a waystation to another emotion.

Not everybody agrees with me; that’s good! If all I thought were things that other people agreed to, I’d think, “Hey! I’m not doing anything that’s very challenging.” I want to do things that people are like, “You believe that? Are you crazy?”

“Yes, here’s the evidence. Here’s why you should believe it. Open up your mind. I want you to see and understand things you didn’t before.” That’s what I want to do.

When it comes to the emotions, what do you find encouraging?

PE: We all make mistakes, but we’ve got these wonderful tools called words. We’re the only animal that has them. They allow us to think about things that we’re not feeling at the moment. That’s an enormously useful tool, if you use it. ‘How I felt,’ ‘what I did,’ ‘why I did it.’ Words let you do that—think about your emotions.

Speaking of people you’ve met through your work, I understand you’ve met the Dalai Lama. How did that come about?

PE: Dan Goleman used to write the science column for the New York Times, and he organized a meeting where he brought eight scientists to spend a week with the Dalai Lama. I was one of the eight. Dan told me later that he regarded me as such a hard-nosed skeptic, he thought I wouldn’t get along with the Dalai Lama. But the Dalai Lama and I reacted to each other like long-lost brothers. He believes that we were brothers in a previous incarnation. I’m agnostic about reincarnation, but I sure know that the Dalai Lama — I feel like he is my brother. We have a wonderful time together. I can’t stop laughing most of the time. He’s a Buddhist monk. I’m a Jewish atheist. You would think we’d have nothing in common, yet we feel like we’re brothers. Another one of the many things about life that I don’t understand, but I’m grateful for.

What do you and the Dalai Lama talk about?

PE: We talk about how to lead a better life. How to lead a life in such a way that it’s of maximum benefit to others. It’s interesting, because it sort of fits the Jewish tradition of a mitzvah. Judaism, the basic tenets are the same as in Buddhism which is, do what you can to help improve the welfare of others. That’s the purpose of life.

What do you hope that people can learn from your research?

PE: I hope that people will understand more about what emotions are, and how to better live with your emotions. They’re not instincts — you do have some choice, but only some. The emotions have their own power, so we need to get on good terms with them, understand them, and have them work for us. Your emotions will sometimes drive you in ways that you don’t want to go, so you’ve got to get well-acquainted with your emotions. Then you’ve got a better chance of having them work with you, not against you.

I recommend people keep a diary, in which they record as much as they can remember about emotional episodes that they’re really happy about, and keep a separate diary of regrettable emotional episodes, in which you wish you hadn’t acted the way you did. Reading those diaries will help you better understand yourself. I mean, that’s the first task of life: understand yourself. The second task is [to] understand others, and how others affect you. That’s what life is about.

Any final thoughts to share?

PE: Always be careful about things you’re doing that you don’t enjoy. Something’s wrong, if you’re not, in some sense, enjoying life. We only live once. Make the most of it.

I’m having a good time, but I’m trying to have my life, at least in part, be of help to others. I think that’s what gives life its greatest meaning.

To learn more about empathy and altruism — and how to cultivate them, check out The Atlas of Emotions.